Needs Pictures: 0

Needs Pictures: 0

Picture(s) thanks: 0

Picture(s) thanks: 0

Results 16 to 30 of 52

-

15th September 2021, 10:51 AM #16

The microbevel size depend on the amount of work the blade has already put in. When the blade is fresh, then the microbevel simply needs to extend across the blade. The wire at the back will tell you that this has occurred.

However, once the plane/blade has been in use, resharpening has also to account for a possible wear bevel on the backmof the blade. The microbevel will be larger as the wear bevel needs to be removed.

Regards from Perth

DerekVisit www.inthewoodshop.com for tutorials on constructing handtools, handtool reviews, and my trials and tribulations with furniture builds.

-

15th September 2021 10:51 AM # ADSGoogle Adsense Advertisement

- Join Date

- Always

- Location

- Advertising world

- Posts

- Many

-

15th September 2021, 10:58 AM #17

Ian, almost inevitably, using a high angle plane - whether BU or BD - will be done in fine cuts, not the thicker shavings of a BD plane with a chipbreaker. So, in part, the finer shavings require less effort.

Secondly, I have many articles, reflecting much research, testing the force in pushing BU planes. Force vectors for BU and BD planes can be markedly different. BU planes have a lowered centre of effort, and this is converted into less force required to push them.

There are articles on my website demonstrating this.

Regards from Perth

DerekVisit www.inthewoodshop.com for tutorials on constructing handtools, handtool reviews, and my trials and tribulations with furniture builds.

-

15th September 2021, 07:11 PM #18

Derek You're ducking & weaving!

I'm assuming the two blades are taking the same shaving - I'm an old research scientist, I only allow you to change one variable at a time. I stand by my assertion that increasing the included angle of the edge of a blade will increase penetration resistance, BU or BD...

I stand by my assertion that increasing the included angle of the edge of a blade will increase penetration resistance, BU or BD...

I cannot see how a lowered centre of gravity can change the amount of actual force required to move the plane forward one jot. It may alter the way you apply effort and change the apparent ease with which you move the plane, but you still have to end up with the same force in the horizontal plane, no matter where you push from....

Cheers,IW

-

15th September 2021, 09:07 PM #19

Hi Ian

No, not "ducking and weaving" - just very little time to respond, and trying to do so as succinctly as possible.

- just very little time to respond, and trying to do so as succinctly as possible.

Remember, I am also a research scientist by training.

The fact is that we are dealing here with a system, that is, several factors working together. We struggle to isolate individual features, as a result, and the more one attempts to do so, the easier these will be shot down by someone else with a different focal point.

If you hold and push a Stanley handle from its upper half, you end up forcing the blade down into the work piece. That is, the force vector is focussed towards the mouth. This will increase resistance ...

This is not how experienced hand planers actually work, but it is a point to note. At the same time, there are some plane designs which make it difficult to avoid this trap. For instance, high sided woodies, such as coffin smoothers also encourage a hand hold where the plane body is pushed downwards.

As I wrote in a number of articles, experienced woodworkers get as low down as possible and push the plane horizontally ...

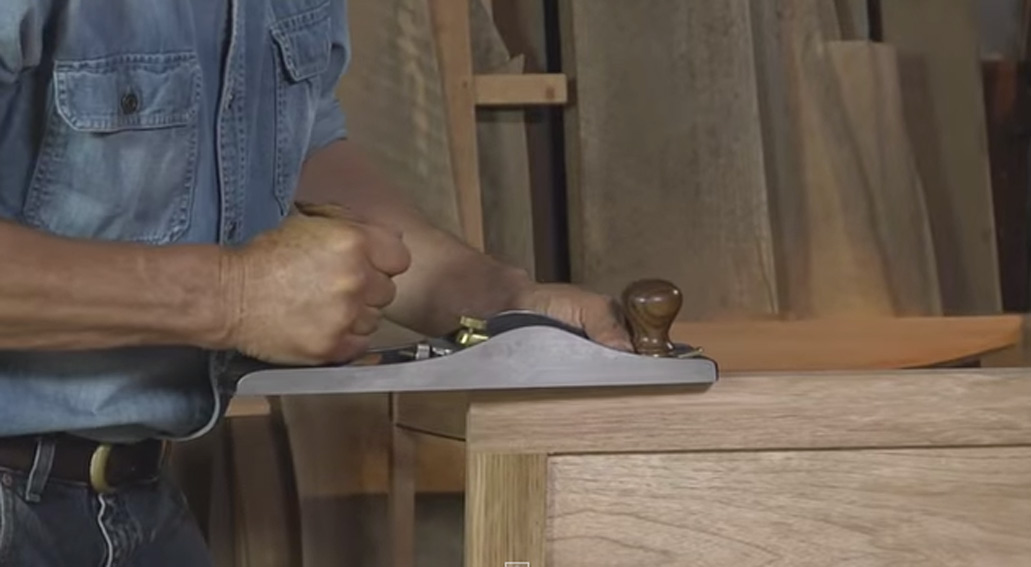

Paul Sellers:

Garrett Hack ...

Frank Klausz ...

David Charlesworth ...

There is a lot of detail here: http://www.inthewoodshop.com/ToolRev...omPlanes3.html

I introduced the concept "centre of effort" in this article: http://www.inthewoodshop.com/Comment...tinaPlane.html

BU planes optimise the combination of low Centre of Gravity and low Centre of Effort. BD planes can be held in a way to create as much of a horizontal force vector, but BU planes do this more naturally - it is not simply the cutting angle, but the orientation of the blade as well ... and the more vertical Veritas handles make this process easier.

The lower cutting angle can be demonstrated to hold an edge longer than a higher cutting angle on a shooting board. When I compared the Veritas Shooting Plane (12 degree BU) and the LN #51 (45 degrees BD), the Veritas even outclassed the LN when it was used with a lower bevel angle (25 degrees vs 30 degrees): http://www.inthewoodshop.com/ToolRev...tingPlane.html

Another factor in the equation with bench planes is bench height. A low bench will encourage down force, while a higher bench will encourage a horizontal push.

What I am trying to show here is that there are several areas to consider when attempting to determine which is easier to push, BU vs BD. This is not simply my opinion, but part of the testing I have done with planes for a couple of decades. I am happy for anyone to disagree, as long as they can show their practical efforts to support their conclusions.

Regards from Perth

DerekVisit www.inthewoodshop.com for tutorials on constructing handtools, handtool reviews, and my trials and tribulations with furniture builds.

-

15th September 2021, 09:07 PM #20

SENIOR MEMBER

SENIOR MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2018

- Location

- Sydney

- Posts

- 469

Doesnt the hang angle on the BU plane handles mean a greater proportion of the force is horizontal compared to the BD planes?

This would affect the impact the blade angles have between the two plane types.

(Looks like Derek beat me to replying ) )

) )

-

15th September 2021, 09:43 PM #21

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

There are two answers to this. Apparently the nicholson text says that the cap iron should follow the iron, but there's not much detail given. I would so don't do it on a plane with a flat sole - it provides no mechanical advantage, but things can go wrong.

Nicholson also thought (I think it was nicholson) that the corners of a double iron plane should be relieved (A wooden one) to avoid clogs. I have been able to make planes of this type for almost a decade now without having any clogging issues just by designing the abutments and fingers correctly. That comment from Nicholson caused Larry Williams to go on at length about how you lose some of the iron width (and for most people in the US to believe it, along with some other fallacies that he held to support the types of planes that he makes).

So I would go with the second answer, which is mine, and probably that of most people working in boat yards - if the sole of the plane has a profile on it (like a gutter plane) but it's a double iron, then the double iron should match the sole of the plane for good tearout control corner to corner.

-

15th September 2021, 09:51 PM #22

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

Derek, I think most of us over here who do most of our work by hand find the opposite - the bu planes aren't any easier to push, they force you to have the plane more in front of you rather than from under to pushing ahead (which lowers efficiency) and they have less of the proper down force angle so they stop cutting earlier. When I was comparing planes testing the "unicorn", I was shocked at how quickly the LN 62 stopped cutting compared to just a basic stanley.

you have to push forward and either unintentionally or intentionally keep some downforce on a plane to keep it in a cut, especially in the right places start and finish, and this has to happen without standing over a plane and bearing down on it or doing much conscious other than a good planing stroke. David Charlesworth has advocated "bracing up" kind of posture, like you would if someone was about to push you and then walking with the plane (because it's probably easier for beginners), but it's bad policy and inefficient. It's debatable whether or not the efficiency matters when few people use planes, that part is fair. I find for the same effort, nothing betters a stanley plane in the metal planes and nothing betters any of the established double iron planes. They generally all have a handle around 60 degrees or so (I haven't measured it in a while as I work off of handle pictures and not angles) to promote rotation of the plane. There's a notion that they have handles like that to work with a low bench, but the two work together to keep the plane in the cut. A continuous cut is the biggest labor saver and it takes some downforce, especially in wood that's hard and the cut is interrupted (like planing out saw marks or skips).

This has historical merit, but I didn't come to it that way. I came to it after going to dimensioning by hand - moderately significant differences in efficiency and design become enormously annoying. Like trying to dimension with single iron planes or do any significant amount of work with bevel up planes. They're awkward once someone gets the hang of the older english or stanley planes - awkward and inefficient. But I can see their draw to beginners or people who plane little - there's not much to figure out.

Of the individuals you showed - Klausz is probably the only one who has done as much planing for purpose as he has teaching it to people. I don't know what hack is doing with his grip, but he'd stop that if he was using the plane long (the tight fist), and klausz is oriented just as you'd expect - he's got his arm pushing into the handle but the handle is providing rotational force by its orientation, and he's standing over the plane and not behind it crouched. If he was using a BU plane, he would have to stand behind it, shorten his stroke and stop to sharpen more often.

Still, even for frank, I don't know how much he actually planed in paying work - but his position is the best of the group. None in that group is my equal with a plane, though all could certainly build better furniture than I can. And they're good at what they do class wise - bringing in beginners.

-

15th September 2021, 09:56 PM #23

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

It does, but it has two problems:

1) it lowers downforce, which is implicit in the posture and handling of typical classic bevel down planes

2) it puts you in a bad posture to really get a good long planing stroke and not have a sort of awkward feeling plane in front of you

It's not a very good plane type for doing more than a little bit of work at a time.

Derek has a picture of his picture on his page - sort of hunched down and behind the plane, but that's sort of a football blocking position. It's not something one would do planing for any period of time.

The dynamic that sticks out to me is whether someone will be in the shop for 3 hours and planing 1 1/2, or if they'll be in the shop switching dust collectors on and off and just planing a little. If it's the latter, they're not going to notice things that become very evident. And what's efficient in a long session turns out to be more efficient in a short one.

wax or wooden soles mitigates any extra downforce contributing to friction in a plane. It's essential that a plane enters and stays in a cut as easy as possible, along with the mechanics of what's going on in a cut. It's also important to get a feel for this stuff by doing - like doing for hours, vs. supposing or drawing pictures. This was an economic enterprise (planing efficiency) 225 years ago, and it wasn't done with posture, bench orientation or handles like we have in BU planes. And when stanley released the BU planes, they didn't sell well - to professionals. That should tell us something.

-

15th September 2021, 10:36 PM #24

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

Not "less recalcitrant woods", but any wood. Any wood that you can plane.

There are some traps in here aside from potentially the issue of using a plane on a shooting board for large pieces (something generally not done) - and that's the idea that something other than a stanley will ultimately be more capable or easier.

I don't have any reasonable size board harder than indian rosewood, but realistically, I doubt anyone is doing much hand work planing the ends of boards with wood harder than indian rosewood. Anything reasonably large is set in the vise upright and then planed like a long edge, and a stanley has no issue with indian rosewood end grain. What I've found so far is that the harshness of end grain generally is limiting to the iron and not to the plane.

The only rosewood board that I have is filled with silica. Planed long grain and "unicorned", an stanley iron will go through the silica without much damage (at least in most cases). With an apex like any typical sharpening method, it destroys all of them in a stroke, and what you're left with is an iron shaving narrow ribbons and within 20 strokes, it's not cutting at all. But the end grain of the board that I planed last night, surprisingly, will cause the silica to still destroy the iron edge, so you get a few nice shavings and then lines. I guess the way it holds silica is different than the way it's held in long grain pores.

If someone was doing a whole lot of hand tool work on something worse than a particularly dense piece of rosewood (rosewood can be all over the board, but the quartered boards that I have for guitar necks are close to 1.0SG, while some of my larger leg blanks are probably only 5-10% more dense than hard maple.

The other trap here is the idea that there's a lot of skill in learning to set the double iron. There isn't - there's a nuance in its use. I set the double iron almost identically on the smoother each time. It's set to straighten a shaving that's about 4 thousandths of an inch - if you push the plane's limits at the set, you might get 5, but the resistance is increasing. That's it. AT that setting, it's better than any single iron plane. It will plane nearly without tearout at 4 thousandths and then you follow that with a pass or two of shavings around a thousandth or 2, depending on the wood (the harder the wood, generally, the less you can get away with because the shavings have more stiffness and will lift).

It's about once or twice a year that I plane something where the cap needs to be set closer, and it's always something like ribboned bubinga or macassar ebony.

I started from a different track - that specialty planes and scrapers were needed and would be more productive, and the lack of them or small number historically had to do with cabinetmakers being too poor to just have whatever they wanted. It is the case that someone willing to use a double iron plane only will quickly learn to see what "the set" is (the one they use 99% of the time) and do the two step smoothing routine I mentioned above - same with a try plane or jointer, etc, and they will be more capable with a single plane than they would have been with an array.

What I can't do for people unless they send me a plane or show up at my door is confirm that their plane is set up fine. But I"ve had 55 degree infills, used 55 degree frogs, set BU planes at 55, and used gordon 55 degree "jack" planes (which were really smoother sized in the type that I had) and none match a stanley, but probably will for a beginner. It's so much nicer having a couple of planes under the bench and just getting through everything efficiently vs. going to the rack back and forth with the feeling like starting and stopping is gaining something.

Lastly, there's a clue to us about what's actually the most efficient in terms of material removal (and why the comparison of the cap iron effectiveness making the equivalent energy used equivalent to a single iron plane with the same effectiveness an incorrect comparison. What do we find in machine planers? Both types - the super surfacer and the tersa type. We don't see an option for a steep approach to the wood, which could easily be done, but rather a combination of lower approach and chipbreaker. Why? its' not simpler. It's just better. The more wood you can get through a machine planer at once with good results, the better its industrial value.

Even the cheap planers with disposable blades have a "chipbreaker bar" holding down the blades. Since they're not settable, they're set reasonably close and they kind of put the brakes on how deep those machines cut, but I"ve hard several professional woodworkers remark that a lot of the lunchbox planers leave a better finish than their large planers - that's because they've never read the instruction manual for their planers to set the variable distance chipbreakers (the fixed ones on lunchbox planers are dummy proof).

I think what beginners may not like (and then get stuck in the same rut their entire life looking for patches or aids) is that you can't really plane for half an hour a week and get any good at it. But you don't have to plane 5 hours a week every week for life to stay good. You have to commit to using planes for something serious or a couple of serious things in a row to get good with them and have them be a subtle feel and look thing rather than constantly looking and thinking about something that should be routine. That commitment is something nobody seems to want to do, but it sure does make things easier afterward. Just like dimensioning wood by sawing makes cutting joints really easy, even though you're not doing any more joint cutting than anyone else does when you do that - it just makes controlling a joinery saw really simple.

(I resigned myself to using double iron planes when dimensioning became too agonizing with the initial group of "foolproof" single iron planes that I had. After wasting a lot of time, I found the double iron planes more capable (And me with them) in a week at most, and without instruction from anyone else - it was findable. Its' kind of embarrassing as I'd built a 55 degree infill with a 4 thousandth mouth 2 years prior and thought it was really ideal - heavy iron, high pitch, tiny mouth ....unbeatable. Unfortunately, it can't control tearout as well as the stanley, it's limited to about half of the shaving thickness that I routinely take with a first pass with a stanley smoother and it probably had to be sharpened about 5 times as often. I would guess the sharpening and setting of the stanley is about 20 seconds more due to the cap iron (not setting it, but taking it apart, etc). It's obviously far more convenient to adjust for the two step smoothing process mentioned above.

Taking 8 passes of 1 thousandth shavings is not tolerable if there's a lot to do when you can take 2 at 4 thousandths and 2 at 1 and get a better result.

It's not a great help that people like cosman and sellers, et al, are big into the idea that the cap iron holds the iron down or that LN calls it difficult to master or fiddly (their interest is in getting beginners going as fast as possible - there's no incentive for them to talk about cap iron preparation and setting - the stream of beginners will never end and it's easier for them to suggest solving with a frog, but a 55 degree frog with the cap set back makes a LN plane a complete dud). Unfortunately, my 55 degree infill is a dud, though it's pleasant to use as a matter of non-project recreation and I can see why they're easy to sell at woodworking shows where individuals using them don't have a clue what they'll be like in real work (they will take that pleasant thin shaving one after another, but you'll miss Church on Sunday if you start a group of door panels saturday evening and resolve not to stop until you're finished with them). And because of the way they have to work, you're constantly out of clearance with them - there's no cap to keep the shaving continuous and you're stuck taking thin shavings - little wear to the edge has to occur.

(I have pictures of my rosewood - they don't tell us much thanks to the silica - you can't gather from them that the first two or four shavings were pleasant and waxy smooth looking because all that's left is destruction from the silica. I have an extremely hard chinese iron that may have the edge strength to get through it - I'll try it later today).

-

15th September 2021, 11:02 PM #25

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

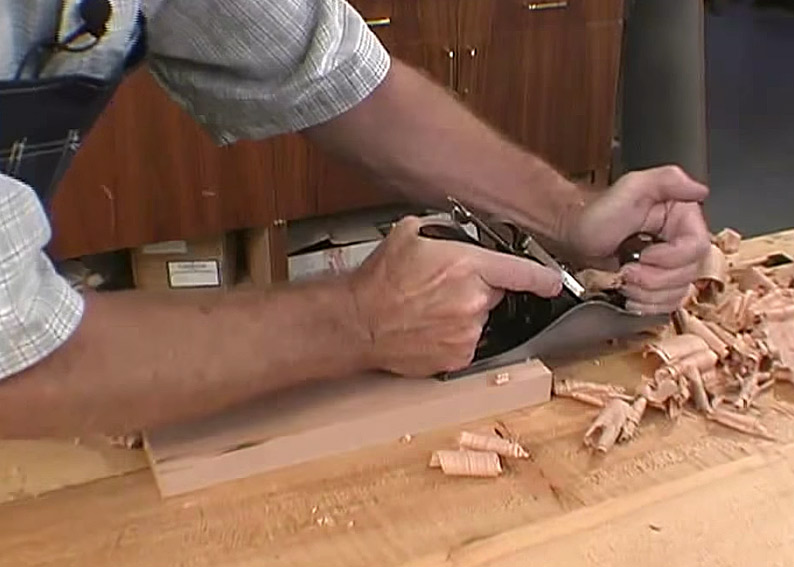

A picture of the rosewood with shavings......

little red arrows pointing out the silica - sometimes these are very small and someone who is a beginner might not notice them at first. I tested a bunch of plane irons two years ago, from O1 to CPM M4 hardened to C64. Nothing survived silica in hard maple (maple is an odd wood - generally wonderfully uniform and the shavings could make rope - smooth and continuous and really strong - but some boards or once in a while in some boards, there are silica/mineral deposits hidden in brown streaks. I have no idea how they form, but up close, the stuff under a scope looks like gray particles of silica).

At any rate, nothing survived it, it's just a matter of whether the edge deflected and the plane stopped cutting or if the deflection chipped out and broke and the plane stopped cutting. The planes that took the smallest damage *visually* with the least amount of work to resharpen out the damage were the harder irons (one japanese blue steel, one chinese iron that was HSS and 65.5 average hardness - despite the aliexpress listing saying it would be 61).

20210915_073123_copy_1441x980.jpg

Notice how wonderful and waxy the shavings are here. This wood would probably janka upper 2000s or 3000 (the typical plantation stuff that's lower density is about 2400-2500, but this is a set of separated quartered wood that was pulled for guitar necks. It's divine...except for the silica (and it wasn't that relatively expensive in the world of guitar stuff - about $90 for 4x1.25x36" boards (fender charges about $700 for a machine made neck of rosewood that looks like a lower cost rosewood).

Annnnyway....

here's the edge of the iron - 1084, relatively high hardness, but 1084 is tough, so what's resultant is a deflection rather than a chip out. The depth of that damage is around 4 thousandths. It's catastrophic. A few of these on an iron spaced apart and the iron will not enter the cut on anything other than jack plane work.

1084 - nicking.jpg

People always think they want tough irons, but what they really want is *strong* irons, and the two are at odds. Other than the fact that you can get back to poor working condition with this iron by honing only part of this off and smashing it back in place with a hard stone at the same time. But the iron won't behave right until the entire depth of damage is removed plus about a thousandth.

here is the identical iron having been worn down through 1000 feet of beech (and ready for resharpening - the "scoop" on the back is visually deeper than it really is, and is from the turn the shaving makes as it is pushed up into the chipbreaker). It takes about 15 seconds of work on a lively washita stone to completely remove this (sometimes this scoop is given as a reason that "Cap irons wear out things faster", but in reality, they don't - they do limit accidental deep scratches that occur from surface dirt, though -without the cap set, those can leave long scratches up the back.

01-284.jpg

At any rate, you can see that instead of just honing this bit down flat (I've found that a good thorough sharpening usually removes about a thousandth) the user of the damaged plane above is stuck doing about 5 times as much work with the potential to create this damage again in a few passes).

So, where am I going with this? When there is talk of planing wood that a stanley plane won't handle, I always question whether or not there's much planing of such a wood, anyway. It's edge damage that limits me, and it gets everything.

I would use this type of wood in an infill plane, but generally, the bed of such a plane is first rough cut with a miter saw or a hand saw, then most of the waste is removed via mortise, and the end grain is perhaps planed a little bit, but always finished with a push scraper to get the bed right.

Industrially, it would probably be trimmed to length in some kind of sanding fixture or by a very light pass with a CNC machine and spiral bit (which is what fender does, and then someone power sands it).

-

15th September 2021, 11:35 PM #26

David, you had better tell all the woodworkers I mentioned that they are also do it wrong. (And, by the way, I am not "hunched down". I am lower as my knees are bent).

Here is Konrad Sauer using one of his planes ...

I watched this video of Rob Cosman yesterday. Look from 4:00 onward ...

Regards from Perth

DerekVisit www.inthewoodshop.com for tutorials on constructing handtools, handtool reviews, and my trials and tribulations with furniture builds.

-

16th September 2021, 12:15 AM #27

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

I wouldn't have any trouble given a volume of wood getting done before them. How many of them do you think have done a serious volume of planing vs. trying to create something beginners can do?

We're not beginners long if we do much volume of work (it's too much effort to continue at that). The reality is that anyone doing a volume of planing would never squat down or flex their knees on purpose - they will stand at a relaxed position, lean over and push the plane out, and then move down the length of whatever they're planing to do the same thing again. long through shavings are only the very last step to confirm a uniform finish on the entire board).

More than once, I've shown David C. where his universal truths about planing aren't that universal, but they can be to an individual if someone wants to believe them.

I doubt you'll find many older engravings showing woodworkers squatting behind a plane - we plane volume, not power per stroke if it creates less volume.

My comments remain the case - they are confirmed by old engravings, and anyone who has done a volume of planing. Klausz in his "dovetail a drawer" takes finishing strokes on drawer sides. He stands in place, over the work with legs relaxed and shifts his weight forward to plane - quickly.

Watch jameel in this video:

Benchcrafted

Jameel has done a lot of planing. I remember Ron Brese mentioning when he made his bench that Jameel showed him up quickly as a "younger man who has a lot of stamina" or something along those lines. I'm sure the stamina part was true, but part of jameel planing a great deal after Ron long since wore out was the way he planes. Relaxed legs, and push through at the end of the thrust. IT's not by accident - it's where you end up if you do more than just smooth now and again.

If what you're talking about was more efficient, the handle orientation and posture in older planes would've been done that way - it's a matter of economics. Efficiency counts for a lot when physical work done converts to currency and you're living on a fairly small surplus. The same is true of sawing - it's a more subtle and less rammy thing dimensioning wood than most show, and it doesn't involve being parallel to the floor and forcing yourself to hold your body weight up like half a pushup. It's over the work at a more subtle posture doing as little as necessary to hold the board and your body oriented.

That's one of the things that irritated me about C.S. early on when literally half of the folks you talked to would come up with "you need to read his books and get his DVDs". He made everything look difficult and awkward.

Harpsichord and Violin Building in the 18th Century (1 of 4) - YouTube

Watch George's posture, watch his waist. He is over the handle of the plane, he never crouches down, but when jointing an edge here, he does not extend his arms at the end. Maybe he found that extension led to less square edges, I don't know (I worked a little on that to be able to extend on jointed edges without twisting the plane - it's easier, but essential). If you watch his waist, though, it doesn't dip when he planes - he's not crouching down and getting behind the plane, he's staying at the same level and leaning over it.

Your advice on this is poor - I know you've stuck to it, and that's your choice, but it's not good advice for someone starting out if they think they may want to do more than just a little with hand tools. I've heard Hack referred to as a guy who makes a piece of furniture and writes a book (it takes longer to write the book) and he can make nice furniture, and he wrote a long book about planes - but that goes to writing a book. I won't repeat everything I've heard, but I have heard more than one person who has done a lot of hand tool woodworking suggest his level of pride is above and beyond his production. That makes people feel like someone is a definitive source (but the grip and the use of a BU plane - other than as a simplified way to get people into woodworking and through his classes - makes it hard to take anything seriously). He boasted to someone once that he was still using the same blades in his thickness planer that he started with. It was a suggestion of efficiency in sharpening them on his part, but realistically, it's a demonstration of the fact that even with machines, his work volume is not high.

DC, same - I mentioned to David that a lot of the things that he does are different than someone will come to if they continue on, and he flatly said that his purpose is to get beginners into something they can succeed at. I appreciated his honesty.

None of those guys looks as comfortable and fluid with planes as Jameel - it's evident to me that at some point, he's done a lot of planing - I don't know what his back story is before making tools other than that he made lute-like instruments and painted idols. But chancing upon that video reminds me of Ron being amazed that he could pick up a plane and pretty much go continuously with it.

-

16th September 2021, 12:20 AM #28

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

one more of someone who at least for a period of time, did all or nearly all of his work with hand tools.

I remember brian emailing me and telling me that he eventually couldn't keep up with orders - almost like he was sorry that he had to get some high grade power equipment (which I told him was cause for celebration -to have so much high-end work that you have to figure out how to do it faster - he lives in a very affluent area, which is probably what allowed him to work by hand for a while in the first place).

Finishing a panel with wooden hand planes - YouTube

Notice the legs and posture. Brian's deliberate and measured, but efficient. I remember seeing him also post one of these on SMC (or someone referenced it) and a couple of "pros" admonished him for allowing the plane to stop in the cut with the try plane. We do it all the time - if the plane is in the cut, it leaves no mark and is easier than hunching down to try to push the plane through like it's a wheelbarrow in a ditch.

-

16th September 2021, 12:22 AM #29

David, I am looking at George at the 3:00 mark, and his planning style looks the same as mine (except that he is LH). It is also notable that he drops his body and lowers his arm until it is parallel with the work piece (lowering the centre of effort).

Brian (in your last post) is very uncomfortable. He planes from his shoulders. A recipe for RSI.

Regards from Perth

DerekVisit www.inthewoodshop.com for tutorials on constructing handtools, handtool reviews, and my trials and tribulations with furniture builds.

-

16th September 2021, 12:40 AM #30

GOLD MEMBER

GOLD MEMBER

- Join Date

- Mar 2010

- Location

- US

- Posts

- 3,112

George is over the plane and pushing forward - we all do the same thing. I haven't paid attention to what I do other than to remember having to go through a transition of the idea that body is rigid and we're pushing from behind and walking with the plane when it's not necessary. That transition is from taking heavier shavings and "Bracing up" to making them about 20% less effort and just standing at a more relaxed posture. It is important to be over the plane and extend out vs. behind it, though - it takes far less energy to shift upper body weight than it does to crouch and dip as you and david charlesworth do.

Charlesworth's interest, again, is to remove variables so beginners have success. I don't think he cares much beyond that as he doesn't advocate much fluid hand tool use - just a collection of short methods to get certain results (his mortising method is also very deliberate and slow - much of what he teaches was learned from Robert Wearing or Wearing's texts).

We absolutely do not want an upright plane handle in any case - being over the place and encouraging rotation by the same angle of the handle is universal from the early english wooden planes through stanley. Only more recently did we get a dippy idea that work benches should be higher and plane handles more straight up.

When you brought this up originally, i remembered having made a bunch of planes, and some of them had handles that were slightly too upright (including Brian H's - I copied and early single iron plane that george identified without even seeing it "they tucked the cutout very far at the top in some early handles, I don't know why", which was true. The plane that I had is a jointer, though, and it was still close to stanley's setup, but I mentioned to brian that he should probably cut it further. It's the only plane I have that's as upright and from a maker who wasn't in business that long.

Planing edges (and faces) straight to slightly hollow - YouTube

So, here's the way that I plane (without thinking about it - something I've come to after planing about, i don't know, 1500 board feet of wood? Not smooth planing, but doing most of the planing from rough - more planing volume than a typical woodworker would get in 15000 board feet).

I'm not pushing from low and behind the plane except that my arm orientation looks like it's parallel to the bench. However the start of the plane is from over and not behind. No squatting, no rigid - you can plane like this all day. It takes not that much time to learn to do it accurately and then you can pay attention to what the plane is doing instead of "planing the ends off of boards" as david C says is the universal truth. I showed him a video suggesting that you can plane boards flat or hollow with through shavings if you do things properly (the downward rotation of these handles pushing from the web of the hand down is critical -but it's natural, you come to it if you do a lot of planing and control the plane subtly rather than in a way that causes fatigue - but it's what people should do from the start).

Similar Threads

-

bevel up planes replacement blade 38 or 50 deg bevel

By justonething in forum HAND TOOLS - UNPOWEREDReplies: 11Last Post: 25th April 2020, 07:15 PM -

N.S.W. Veritas Bevel up Smoothing Plane - Free Postage

By D-Type in forum WOODWORK - Tools & MachineryReplies: 3Last Post: 16th December 2017, 12:30 PM -

Bevel Down Chariot smoothing planes did they exsit

By Kate84TS in forum WOODWORK - GENERALReplies: 0Last Post: 28th June 2017, 05:37 PM -

The Veritas Bevel Up Smoothing Plane

By chook in forum HAND TOOLS - UNPOWEREDReplies: 18Last Post: 24th June 2012, 12:40 AM -

Bevel Up Planes With Back Bevel

By Termite in forum HAND TOOLS - UNPOWEREDReplies: 21Last Post: 17th August 2005, 08:46 AM

Thanks:

Thanks:  Likes:

Likes:

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote